Travels in Mexico

Amy in the

Jardin Etnobotanico

In late November 2003 I traveled to Oaxaca in the southern Mexican highlands, the legendary home of cochineal. For well over a year before I made the journey, I’d corresponded with some wonderful Oaxaqueños about the history and cultural traditions involving the dye. But nothing could compare with meeting people face to face and seeing cochineal used in its ancient homeland.

Here are some photos from that trip, taken by Eric Mindling and by my husband, David Greenfield. I’ve provided captions and commentary.

The Jardín Etnobotánico is Oaxaca City’s magnificent garden of native plants. Under the painstaking care of Dr. Alejandro de Ávila, the garden flourishes behind the high walls of the old Dominican monastery. (Now a noted museum of Oaxacan history, the monastery itself is a work of art, with cloisters and stone staircases and wide windows that frame vistas of stark mountains and clear skies.)

Alejandro was one of my most helpful correspondents as I was writing the book, and it was a joy to finally meet him in person. My husband and I accompanied him on a tour of the garden. He showed us wild cochineal nestling against cacti, and he plucked leaves from the Oaxacan herbs for us to taste. Pointing out the wild maize and squash plants, he explained that Oaxaca was a cradle of American agriculture. Archaeologists working in the state have found the oldest known samples of domesticated maize and squash — dating back about ten thousand years and six thousand years respectively.

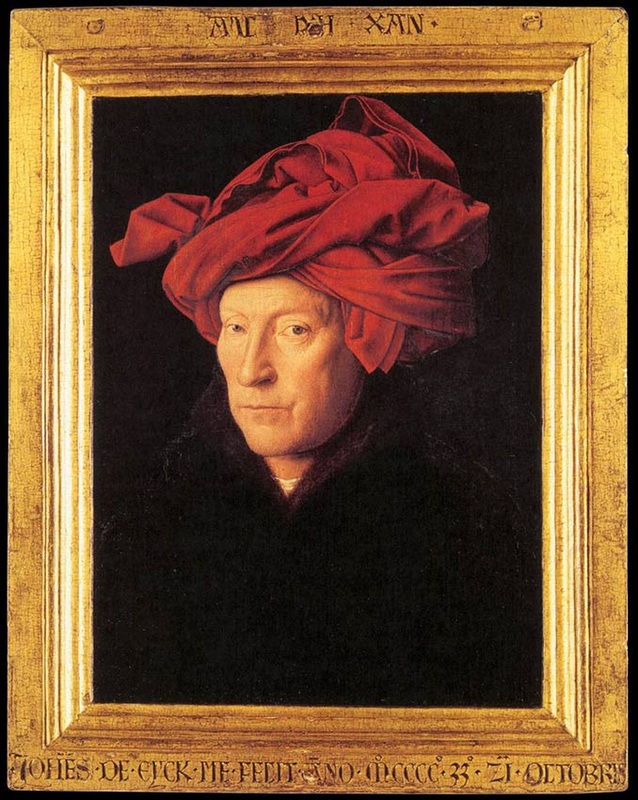

In this photograph I’m standing by a fence made of living cacti. In the background is a prickly pear, also known as the opuntia or nopal cactus — favorite food of the cochineal insect. Mexicans sometimes used to surround their prickly pears with fences made from other species of cactus in order to protect the cochineal from marauding livestock and other predators.

Ingeniero Ignacio del Rio Duenas,

Owner of Tlapanochestli

In the twentieth century, the cochineal industry all but vanished from Mexico, and cochineal itself nearly died out. But these days Mexican cochineal has new champions, and one of the chief of these is Señor del Río. Known to his friends as Don Nacho, he is reviving the cochineal business at Tlapanochestlí, a farm in Santa María Coyotepec, which is a village just south of Oaxaca City. On a fine winter Saturday, Eric Mindling, David, and I drove down to Coyotepec to see Tlapanochestlí, and we were bowled over by his energy, charm, enthusiasm, and knowledge of cochineal.

If you travel to Oaxaca, the nopalry and its museum are well worth a visit. You can buy bags of cochineal, cakes of cochineal dye, and cochineal ink in the Tlapanochestlí shop.

A Tlapanochestli Cactus Shed

This photo was taken when I was standing inside one of the sheds that Don Nacho uses to shield his cacti and cochineal from the winter weather. Traditionally the cacti and cochineal were grown out in the open, but cochineal is a very fragile creature, and you could easily lose your cochineal harvest to an ill-timed tempest or sudden fall in temperature. By growing it inside this shed framework, Don Nacho is able to open everything up to the sun on warm days, then close it on cold nights. The weekend that we visited was the coldest weekend of the year, so the shed is completely covered in plastic sheeting.

Nopal Cacti at Tlapanochestli

This gives you a better sense of how a nopalry normally looks. (Note, however, that these cacti don’t have any cochineal growing on them. That’s why they could be safely left out in the open despite the cold.)

Cochineal Seeding

This is a good view of what’s called the "seeding" of cochineal. Baskets containing the mother insects and their young are attached to the nopal, and the tiny young cochineal insects swarm over the cactus.

Cochineal on the Cacti

Some say that cochineal looks like bits of cotton fluff caught on the cactus. Others think it looks more like a fungus. What it doesn’t look like is an insect, because all you see is the waxy white outer coating that the cochineal makes to protect itself. The insects don’t move around, but simply slip their beaks into the cactus and settle in for good.

Live Cochineal in the Hand

A cochineal in the hand is worth two on the cactus — A live Dactylopius coccus, fresh from the pad.

Cochineal Grinding

Some of the best natural dyers working in Mexico today are Fidel Cruz and his wife, María Luisa Mendoza. They live on the outskirts of a town south of Oaxaca City called Teotitlán del Valle, which is famous for its weaving. Most of the colors in Teotitlán rugs and textiles are made with artificial dyes, but a few top-rank dyers like Fidel and María work with old-fashioned natural dyes. Their red dyes are derived from Mexican cochineal, some of which is supplied by the Tlapanochestlí nopalry.

Here you can see María grinding the cochineal on her stone mortar, or metate. Her hands move so quickly that they blur. When she’s finished, the cochineal powder goes into the dyebath, along with several other ingredients that fix, darken, and intensify the color: alum, acacia fruits, and freshly squeezed lemon juice.

Putting Wool in the Dyepot

Fidel prepares to lower the wool yarn into the dyepot. The three different shades you see are inherent in the wool itself, which has never been dyed before.

Wool Soaking in the Pot

The wool soaks in the steaming dyepot for hours.

Checking for Color

Every so often, Fidel draws the fibers out, then dunks them back in again, patiently waiting for the color he wants. Like the master dyers of the Renaissance, he relies on both instinct and judgement to obtain the right shade.

A Perfect Red

Used with judgement, experience, and skill, cochineal yields a perfect ruby red.

Strung across the hard-packed open courtyard of Casa Cruz, scarlet skeins of wet wool hang dripping.

On the Line

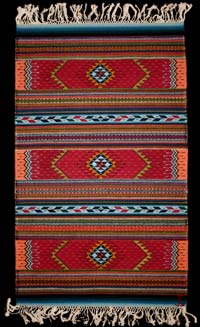

This tapete or rug was recently woven by Fidel Cruz, who has won national awards for his work. All the colors come from natural dyes, and the intense fuchsia reds come from cochineal.

Like Fidel and María, a number of Oaxaca's best dyers and weavers have returned to using locally-produced cochineal, despite the great cost. In their intricate rugs and weavings, the cochineal reds glow and shimmer — a colorful symbol of an ancient legacy that lives on.

Cochineal Tapete by Fidel Cruz